Introduction

India is one of the world’s most intricate language ecosystems. India recognizes 22 scheduled languages in the Constitution, while the 2011 Census recorded 121 languages and more than a thousand additional “mother tongues” once local naming and clustering are accounted for. No single tongue fully dominates public life.

Instead, people routinely navigate layered repertoires: a home language, a regional language for school and local media, Hindi or English for wider communication, and sometimes another language for migration, religion, or work.

Understanding how this mosaic works is not academic trivia. It shapes education outcomes, trust in digital services, content reach, and the success of technology products and translation strategies.

Source: Map of India

Why So Many Languages Persist

Historical and Structural Overview

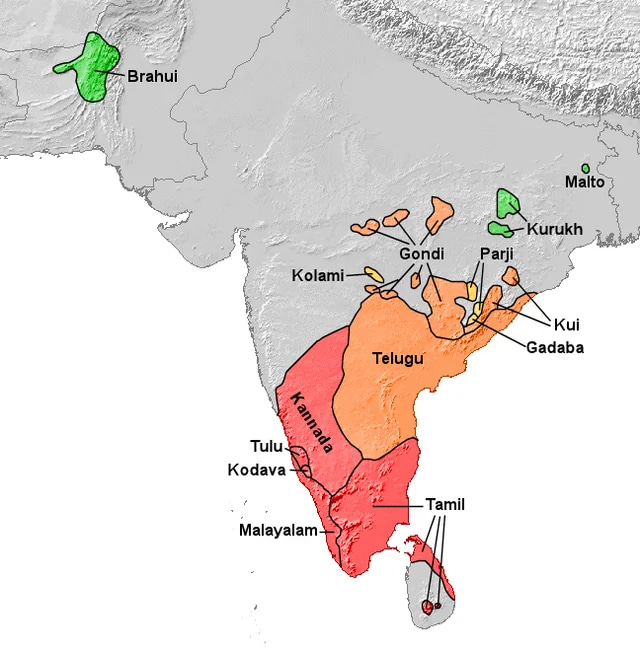

- India’s linguistic backbone consists of Indo‑Aryan languages in the north, west, and east, and Dravidian languages in the south.

- Tibeto‑Burman languages are spoken in the Northeast, while Austroasiatic (Munda) languages exist in central and eastern tribal belts.

- Long-term interaction among these groups has led to shared structural features such as retroflex consonants and postpositions.

English and Policy Influence

- English was introduced as an administrative and legal medium and remains a practical bridge in higher courts, federal communication, and higher education (Official Languages Act, 1963).

- Mid-20th-century linguistic state reorganization aligned many state boundaries with dominant regional languages.

- There are ongoing discussions about recognizing additional languages such as Bhojpuri and Tulu, since recognition brings funding and educational support.

Speaker Population Estimates

(Derived from census baselines and later surveys such as Ethnologue)

(Derived from census baselines and later surveys such as Ethnologue)

| Language | Native Speakers in India | Global Total / Notes |

| Hindi (incl. varieties) | 340 million | >600 million total users |

| English | small native base | 125–135 million functional users |

| Bengali | 100 million | >230 million including Bangladesh |

| Telugu | 95 million | – |

| Marathi | 80+ million | – |

| Tamil | 78 million | – |

| Gujarati | 62 million | – |

| Urdu | 50 million | ~70 million worldwide |

| Bhojpuri | 50 million | Not in Eighth Schedule |

| Kannada | 45 million | – |

| Malayalam | 38 million | – |

| Odia | 35 million | – |

| Punjabi | 35 million | >120 million global |

| Assamese | 15 million | – |

| Maithili | 13 million | – |

| Santali | 7 million | – |

Several forces prevent consolidation into a single national vernacular. Regional film and television industries (Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Bengali) reinforce prestige and economic demand. Deep literary traditions in Tamil, Bengali, and Sanskritized Hindi sustain formal registers. Religious and cultural domains maintain Urdu, Sanskrit, and classical Tamil or Malayalam styles.

Internal labor migration mixes speakers in metros like Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Delhi, yet code‑switching often supplements rather than replaces mother tongues.

Social media accelerates “Hyphenated Englishes” such as Hinglish (Hindi plus English elements) and Tanglish (Tamil plus English), normalizing fluid bilingual creativity without erasing base grammars.

Mutual Intelligibility in Practice

Hindi–Urdu: Shared Speech, Divergent Scripts

Hindi and Urdu share an oral Hindustani core, making everyday conversation broadly intelligible. Yet at higher registers, Hindi leans on Sanskrit-derived vocabulary, while Urdu draws on Perso-Arabic terms. Their scripts—Devanagari for Hindi and Nastaliq for Urdu—are entirely different, creating a barrier in literacy and digital applications.

In translation markets, this divergence is especially evident: English→Hindi drives government portals, fintech, and e-commerce, while English→Urdu and Hindi→Urdu require not just lexical mapping but also script conversion and register sensitivity.

Hindi and Its Neighbors: Partial Overlap

Within the Indo-Aryan belt, adjacency fosters partial comprehension. A Hindi speaker may follow parts of a Maithili or Bhojpuri exchange, but deeper syntax and phonology reduce understanding over longer discourse. With Bengali, Odia, or Assamese, structural similarities exist, yet spontaneous intelligibility is minimal.

Commercially, English→Bengali is crucial for banking and news media in eastern India, while Hindi→Bengali or Hindi→Marathi appears in regional syndication and educational content.

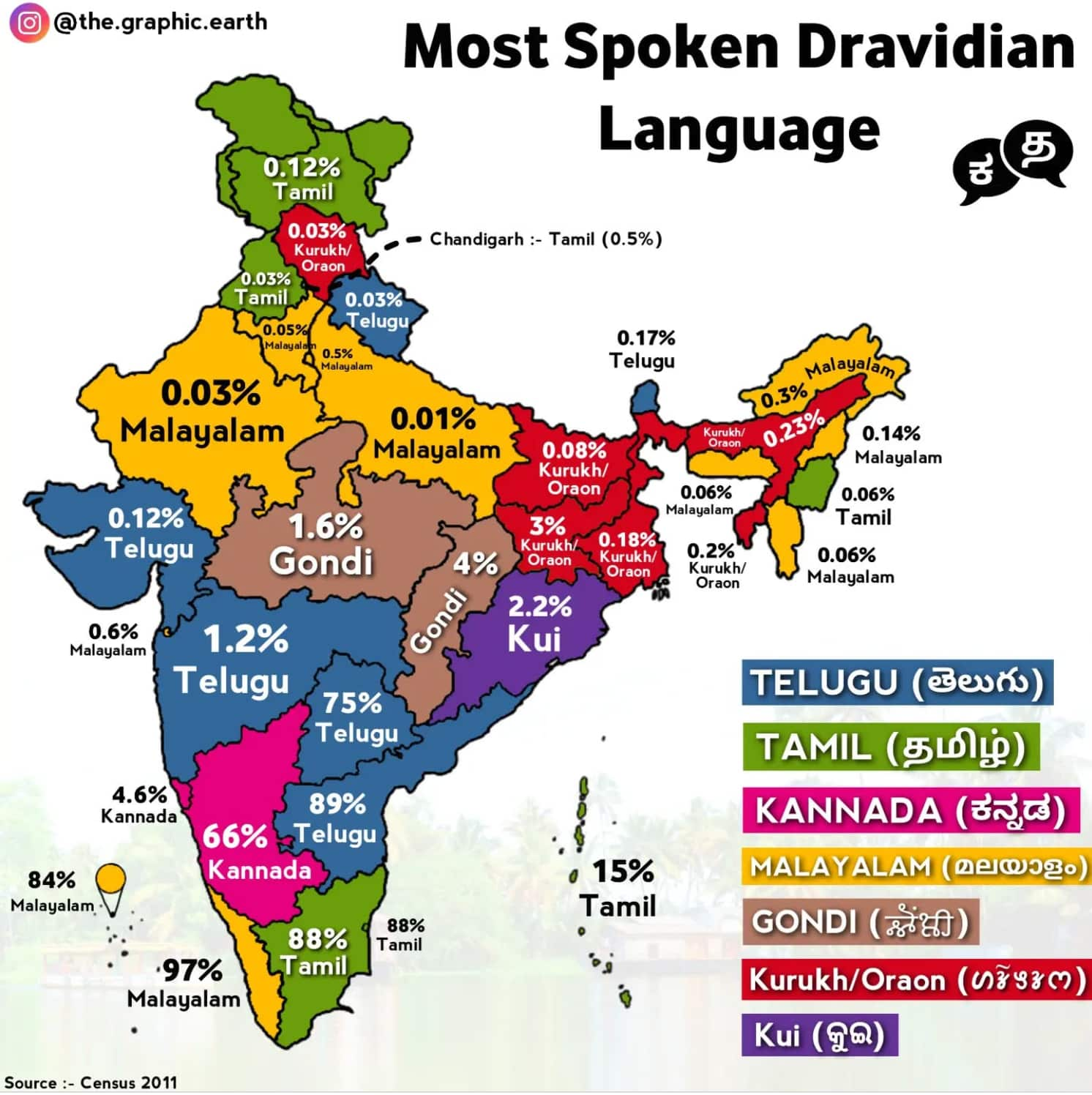

Dravidian Pairs: Structural Affinities

Among the Dravidian languages, closer internal pairings are visible. Tamil and Malayalam share a substantial historical base and display relatively high mutual intelligibility. Kannada and Telugu show strong structural parallels, though vocabulary overlap in casual speech is lower, limiting comprehension without prior exposure.

These southern languages also dominate digital translation demand:

- English→Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam serves technology and entertainment, especially streaming subtitles and app interfaces.

- Arabic→Malayalam or Tamil supports labor contracts and remittance services in the Gulf migration corridor.

Across Families: Gaps and Bridges

Between the Indo-Aryan and Dravidian families, spontaneous mutual understanding is virtually absent. In multilingual cities such as Bengaluru and Hyderabad, speakers bridge gaps by relying on English or Hindi, while local languages thrive in cultural and domestic contexts.

In practice, English→Marathi, Gujarati, and Punjabi translation underpins small business finance, e-commerce support, and customer service across western and northern states. Gujarati, Punjabi, and Hindi also extend into the diaspora, reinforcing the need for high-volume translation pipelines.

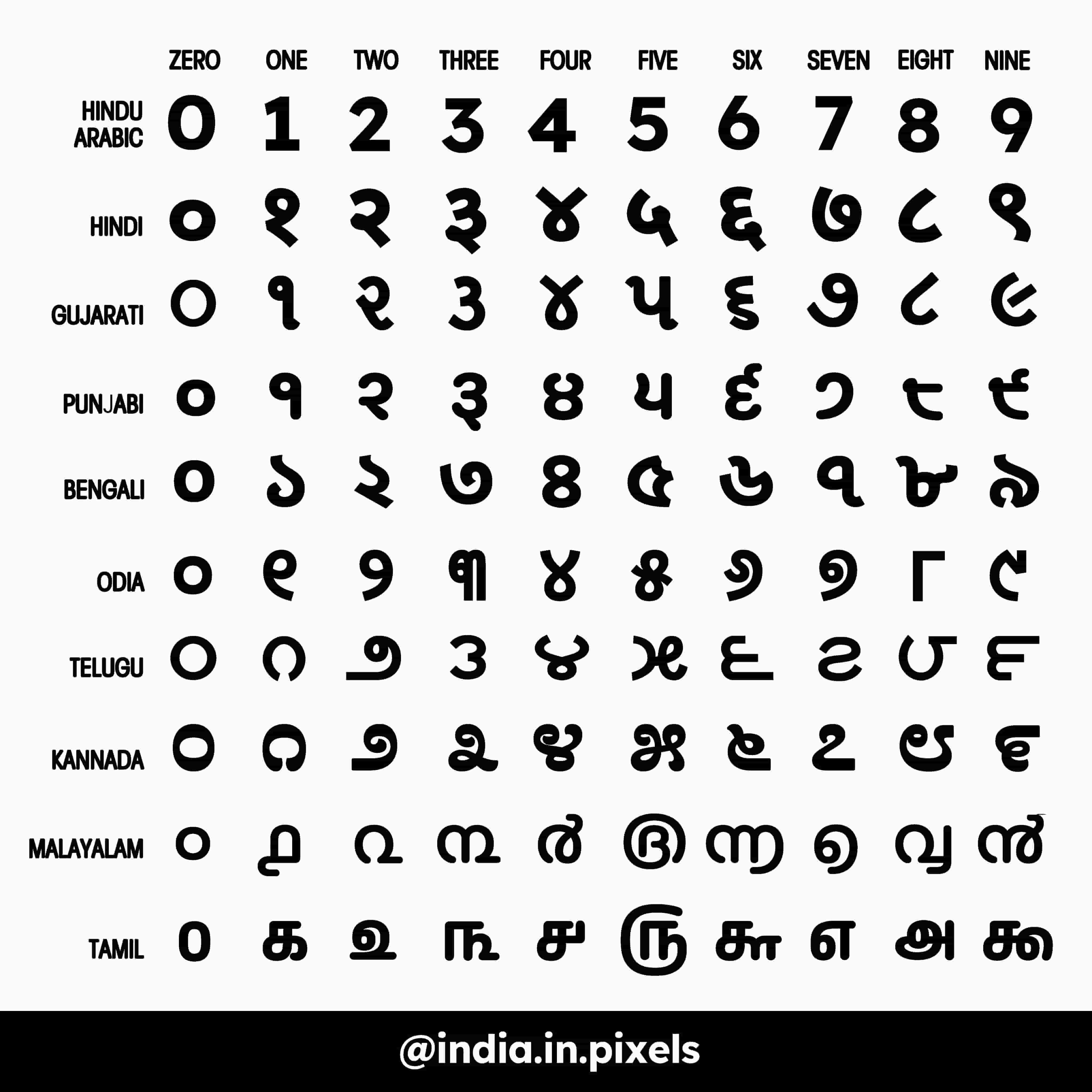

Scripts and Communication Challenges

India’s languages are written in a variety of scripts, which multiply the complexity of digital and print communication. Devanagari is used for Hindi and Marathi, while the Bengali-Assamese script covers Bengali and Assamese. Other major scripts include Gurmukhi for Punjabi, Gujarati, Odia, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, and Tamil. Perso-Arabic Nastaliq is used for Urdu and Kashmiri, and Ol Chiki is used for Santali.

Script choice influences font support, search indexing, and machine translation quality. Urdu in Nastaliq, with its diagonal flow and context-shaped letters, brings layout and rendering challenges distinct from the more linear Indic scripts.

Source: Examples-of-Indian-Scripts

Script diversity further separates communities: Devanagari, Bengali-Assamese, Gurmukhi, Dravidian scripts, Nastaliq, and Ol Chiki represent distinct writing systems. While Roman letters often appear in texting and online search (“namaste,” “vanakkam”), script choice still affects literacy, font support, search indexing, and machine translation quality.

This complexity shapes translation workflows:

- Reversible script conversion layers (e.g. Devanagari ↔ Perso-Arabic for Hindustani vocabulary).

- Language identification for code-mixed social media.

- Locale-aware formatting for numbers and currency.

- Honorific tagging in MT pipelines.

- Transfer learning and synthetic data for low-resource languages like Santali or Tibeto-Burman tongues.

- Evaluation beyond BLEU, considering script rendering, register appropriateness, and named entity accuracy.

Geographical and Diaspora Spread

Inside India, linguistic regions show clear geographic patterns. Northern and central India, often referred to as the Hindi-speaking region. The east centers on Bengali, Odia, and Assamese, the west on Gujarati and Marathi, and the south on the four major Dravidian languages: Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, and Tamil.

Tribal belts in central and eastern regions host Munda languages, while the Northeast is a mosaic of Tibeto‑Burman languages and recognized state languages such as Manipuri (Meitei) and Bodo.

Tribal belts in central and eastern regions host Munda languages, while the Northeast is a mosaic of Tibeto‑Burman languages and recognized state languages such as Manipuri (Meitei) and Bodo.

Urban Multilingual Hubs

Major Indian cities act as multilingual switching hubs, where regional and national languages coexist with English:

- In Bengaluru, one hears Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, Hindi, and English.

- In Hyderabad, Telugu, Urdu, Hindi, and English share space.

- In Mumbai, Marathi and Hindi anchor public life, while Gujarati and English thrive in commerce.

(Suggested image: urban multilingual city infographic.)

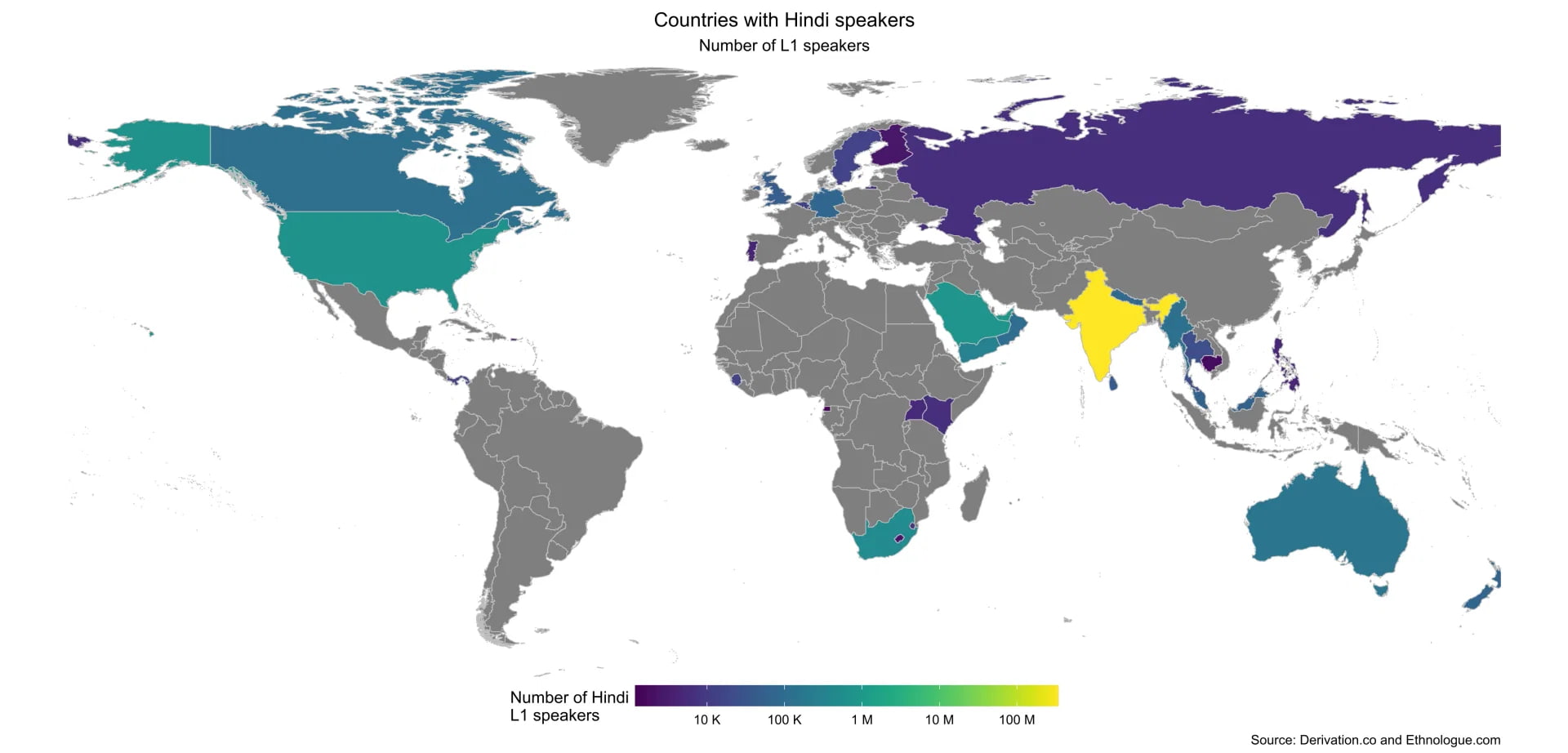

Hindi

Hindi is the most widely spoken language in India, with roughly 340 million native speakers and over 600 million total users including second-language speakers. It dominates the Hindi Belt in northern and central India and is widely understood across the country as a lingua franca.

Overseas, Hindi-speaking communities exist in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, East Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, Suriname, and the Caribbean, often coexisting with English or French among second-generation migrants.

Bhojpuri and related Hindi varieties, though not officially recognized in the Eighth Schedule, survive in several overseas communities.

Overseas, Hindi-speaking communities exist in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, East Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, Suriname, and the Caribbean, often coexisting with English or French among second-generation migrants.

Bhojpuri and related Hindi varieties, though not officially recognized in the Eighth Schedule, survive in several overseas communities.

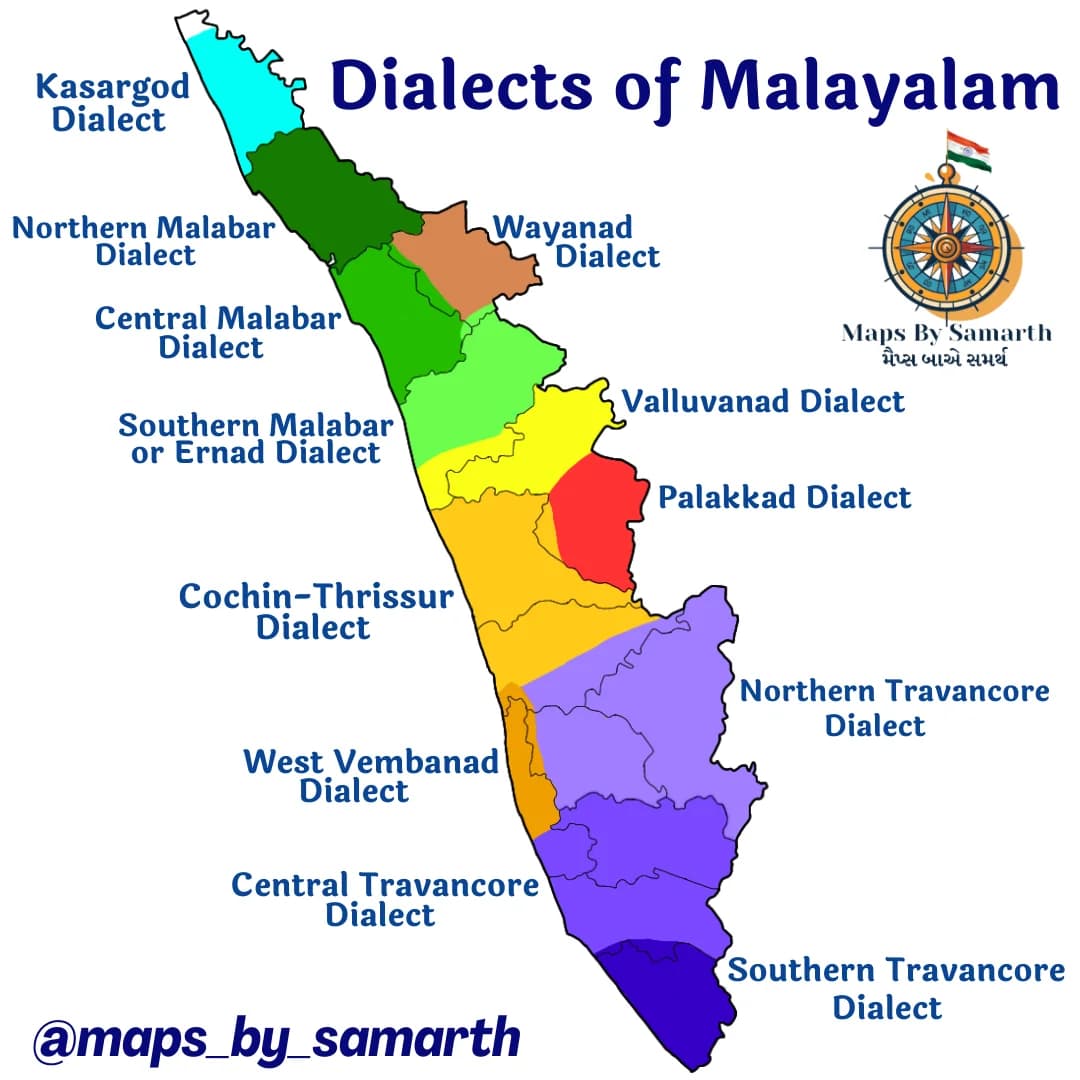

Malayalam

Malayalam is spoken primarily in Kerala, with around 38 million native speakers. Overseas, it is prominent in Gulf labor corridors, where migrant communities maintain daily communication in Malayalam.

Second-generation diaspora often shift toward English but retain ritual and cultural practices in Malayalam.

Second-generation diaspora often shift toward English but retain ritual and cultural practices in Malayalam.

Telugu

Telugu (~95 million native speakers) dominates Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. In urban centers like Hyderabad, Telugu coexists with Urdu, Hindi, and English.

Internationally, Telugu-speaking communities are found in Canada, the United States, and Australia, where cultural associations and community events help retain language and traditions among second-generation migrants.

Internationally, Telugu-speaking communities are found in Canada, the United States, and Australia, where cultural associations and community events help retain language and traditions among second-generation migrants.

Kannada

Kannada (~45 million native speakers) is concentrated in Karnataka. In Bengaluru, it interacts with Tamil, Telugu, Hindi, and English, reflecting urban multilingualism.

The overseas Kannada diaspora is smaller but present in North America, the United Kingdom, and the Gulf, maintaining cultural and linguistic ties through associations and community gatherings.

The overseas Kannada diaspora is smaller but present in North America, the United Kingdom, and the Gulf, maintaining cultural and linguistic ties through associations and community gatherings.

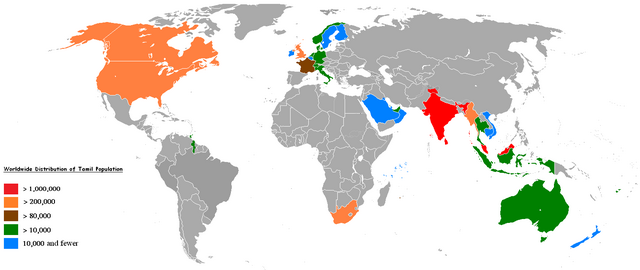

Tamil

Tamil (~78 million speakers) is spoken in Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, and across parts of Sri Lanka. Beyond South Asia, Tamils form one of the most widespread Indian diasporas, numbering around five million worldwide.

The largest overseas communities are in Malaysia (about 1.9 million) and Singapore, where Tamil enjoys official recognition. Substantial populations are also found in the Gulf states, South Africa, Canada, the United States, Australia, and across Europe.

The largest overseas communities are in Malaysia (about 1.9 million) and Singapore, where Tamil enjoys official recognition. Substantial populations are also found in the Gulf states, South Africa, Canada, the United States, Australia, and across Europe.

The global spread of Tamil reflects several historical and economic phases: colonial-era indentured labor migration to Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean; 19th-century movements linked to trade and labor opportunities in Malaysia, Singapore, and Mauritius; and later professional and educational migration to North America, Europe, and Australia.

Within these communities, language maintenance is a defining feature. While younger generations often adopt English or local majority languages in daily life, Tamil remains vibrant through temples, community schools, cultural associations, and media networks.

Cinema, digital platforms, and traditional performances help transmit the language across generations, ensuring cultural continuity.

As a result, Tamil identity remains deeply rooted in language practice, both in its South Asian heartland and in diaspora communities worldwide.

Cinema, digital platforms, and traditional performances help transmit the language across generations, ensuring cultural continuity.

As a result, Tamil identity remains deeply rooted in language practice, both in its South Asian heartland and in diaspora communities worldwide.

Typical Pitfalls

Common mistakes include assuming “Hindi equals India” and neglecting Tamil, Bengali, or Malayalam users; enforcing a single formal register where a colloquial voice would improve engagement; overusing untranslated English technical words that erode trust; miscalculating financial figures by ignoring lakh and crore; or treating Hindi and Urdu as either fully interchangeable (ignoring literary and religious nuance) or entirely separate (duplicating effort where shared resources could help).

Poor font choices can also degrade readability in Nastaliq (Urdu) or in complex conjunct clusters in Malayalam and Kannada.

Poor font choices can also degrade readability in Nastaliq (Urdu) or in complex conjunct clusters in Malayalam and Kannada.

Strategic Takeaways

India is one of the most linguistically diverse places in the world, with 121 officially recognized languages and more than a thousand mother tongues. No single language dominates; people move fluidly between home, regional, national, and global languages.

The mix of Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, and Munda families, along with many scripts, diaspora communities, and code-mixed speech, makes communication both a challenge and an opportunity.

The mix of Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, and Munda families, along with many scripts, diaspora communities, and code-mixed speech, makes communication both a challenge and an opportunity.

Translation needs reflect this variety: English with Hindi for government and commerce, English with Bengali for finance and news, English with Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam for technology and entertainment, English with Marathi, Gujarati, and Punjabi for small business, and Arabic with Malayalam or Tamil for Gulf-based work and remittances.

Work between Hindi and Urdu, or Hindi and Bengali and Marathi, also depends on script conversion and sensitivity to style and register. Meeting these needs requires more than just word-for-word accuracy. It takes awareness of honorifics, code-mixing, script handling, and cultural tone.

Work between Hindi and Urdu, or Hindi and Bengali and Marathi, also depends on script conversion and sensitivity to style and register. Meeting these needs requires more than just word-for-word accuracy. It takes awareness of honorifics, code-mixing, script handling, and cultural tone.

VMEG AI’s Role

VMEG AI is built to help with exactly this. It makes communication smoother both between Indian languages and between Indian and global audiences. With features like script conversion, high-quality speech translation, and culturally aware adaptation, VMEG AI helps governments, businesses, and creators reach people more naturally across India’s linguistic landscape.

Connect with Millions across India!

VMEG now supports video translation for India’s major languages: Bengali, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. From education and business to global content outreach, communicate seamlessly across India’s diverse audiences.