Introduction

Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua / Standard Chinese) is the world’s most widely spoken first language and one of the six official languages of the United Nations (United Nations). Depending on methodology, estimates place native speakers around 920–960 million, with total users (native + second language) exceeding 1.1 billion.

It underpins the largest single community of internet users, powers supply chains and innovation hubs, and increasingly shapes global culture through film, gaming, literature, and short‑form video (DataReportal 2024). For organizations expanding internationally, understanding Mandarin’s structure, variation, and localization nuances is now a strategic competency.

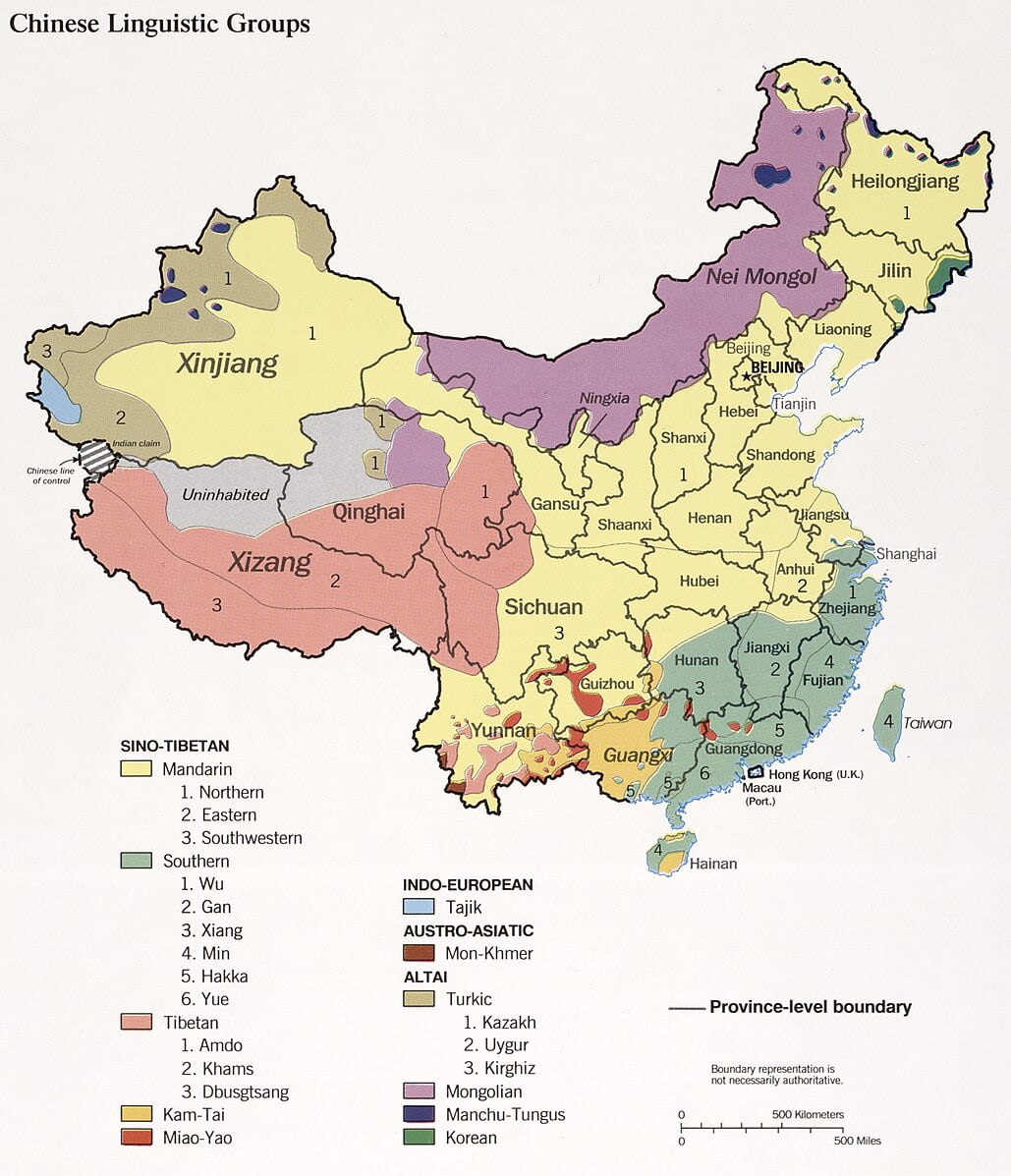

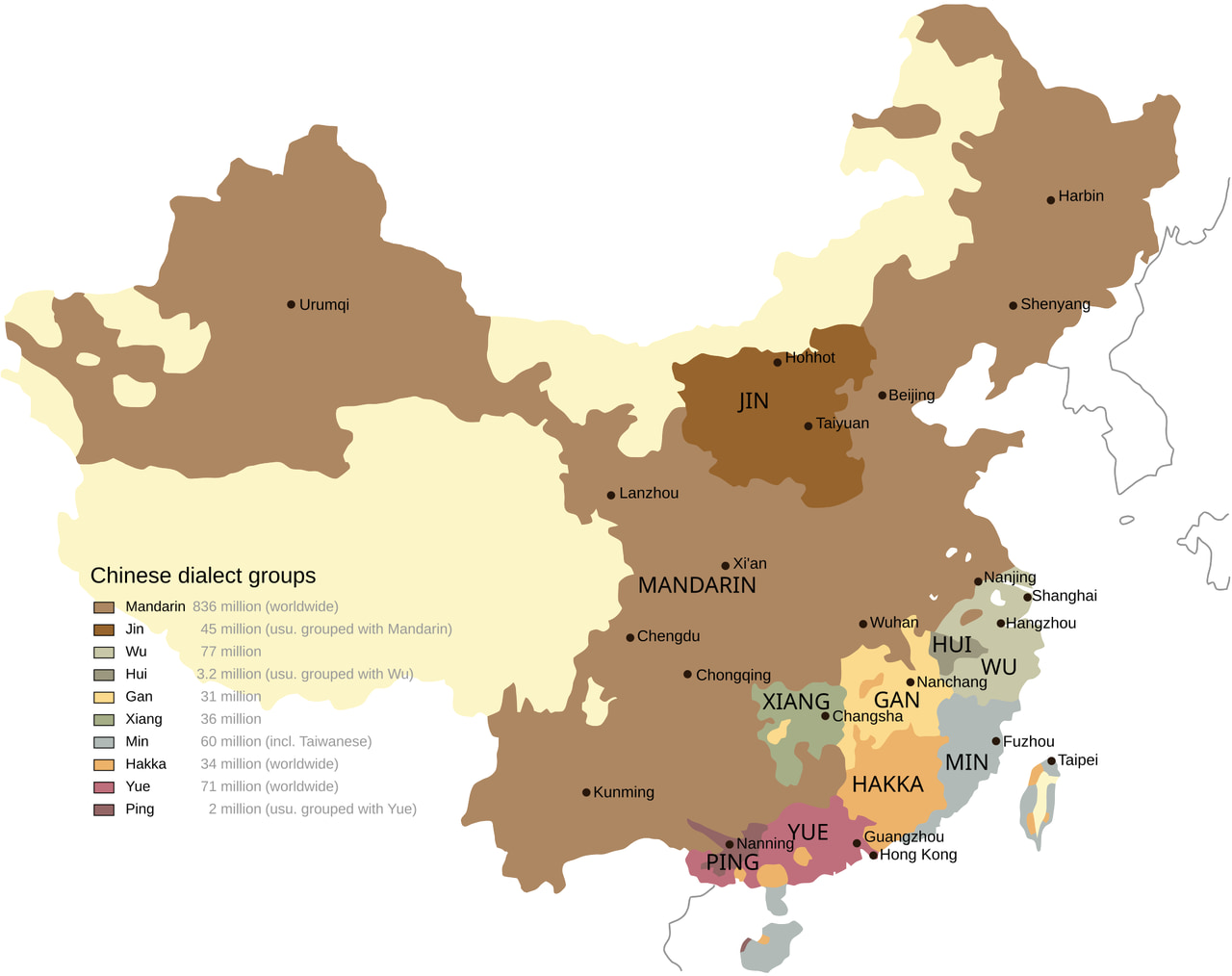

Chinese and Its Varieties

“Chinese” comprises a family of Sinitic lects—Mandarin, Cantonese (Yue), Wu (e.g., Shanghainese), Min (e.g., Hokkien, Teochew), Hakka, Gan, Xiang, and others—many of which are mutually unintelligible despite shared classical written heritage.

Mandarin functions as the national common language in the Chinese mainland and as a prestige lingua franca across diasporic Chinese communities.

Its UN working-language status supports its role in diplomacy and international governance. China’s economic rise—second in nominal GDP and first in PPP-adjusted manufacturing output (World Bank 2023) has accelerated demand for Mandarin in trade, technology partnerships, standards negotiations, and supply chain coordination.

Source: Chinese Linguistic Groups

Major Dialects of Mandarin Chinese

Within Mandarin itself, scholars identify a spectrum of regional dialect groups that reflect both geographic history and social identity.

Major subdivisions of Mandarin include:

- Northeastern Mandarin – Broad vowel qualities and a relatively “open” tone system.

- Beijing Mandarin – Prestige dialect forming the basis of the national standard; notable for rhotic suffixation (erhua).

- Ji–Lu Mandarin (Hebei, Shandong) – Retains conservative tonal patterns.

- Jiao–Liao Mandarin (Liaodong & Shandong peninsulas) – Influenced by maritime trade contacts.

- Zhongyuan Mandarin (Henan, Shaanxi) – Historically central to Chinese drama and literature.

- Lan–Yin Mandarin (Gansu, Ningxia) – Shows contact features from Turkic and Tibetan languages.

- Jianghuai Mandarin (Nanjing, Anhui) – Often noted for softer consonant distinctions.

- Southwestern Mandarin (Sichuan, Chongqing, Yunnan, Guizhou) – Fewer tone contrasts and widespread lexical innovations.

Although grouped under the “Mandarin” umbrella, these dialects diverge enough in phonology and vocabulary that communication across distant regions can be difficult without prior exposure.

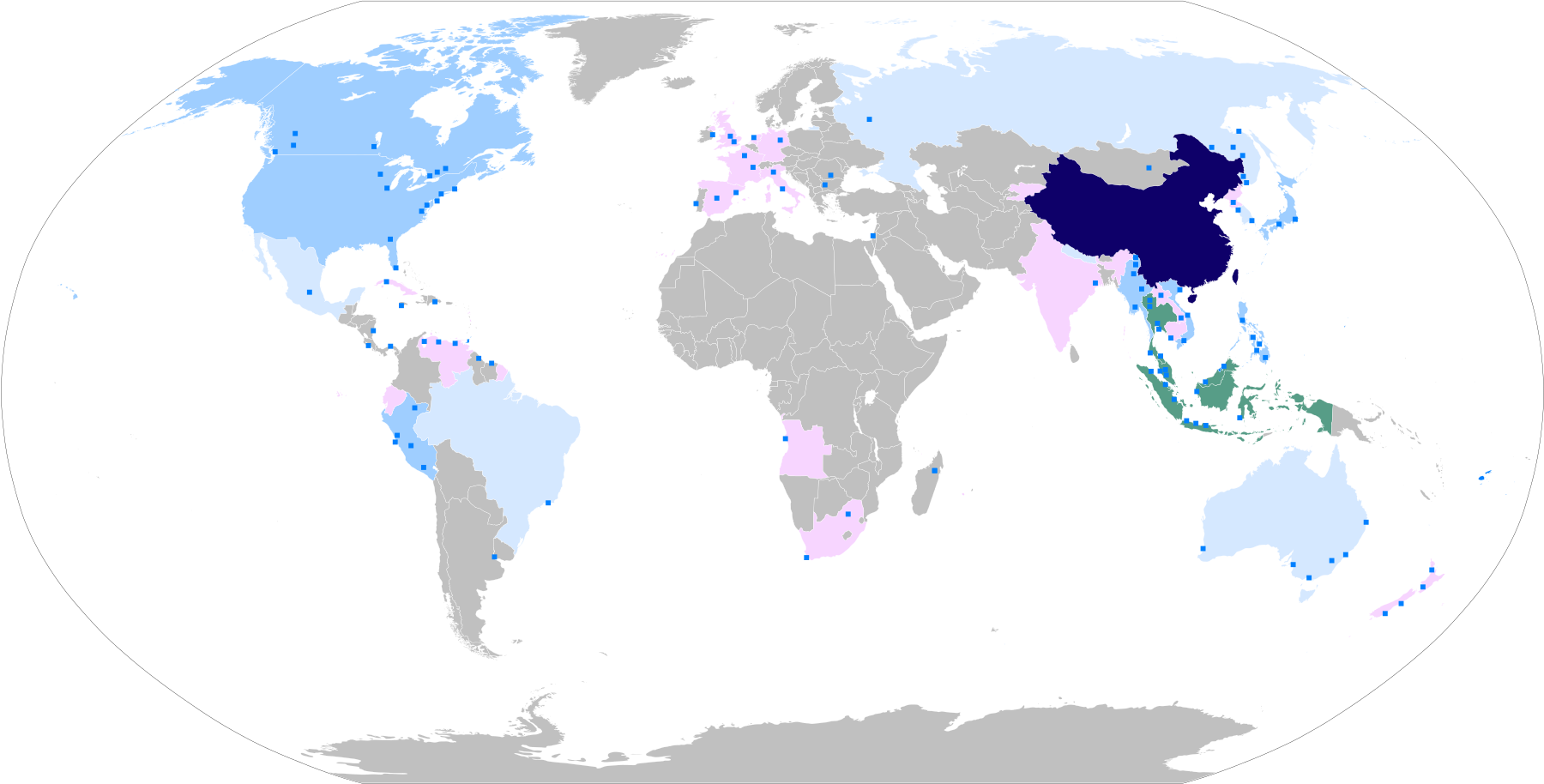

How Many People Speak Mandarin In The World?

Mandarin is a standard language. It is nobody's native language, but a good average between various language forms and a common language everyone can understand and communicate with.

Roughly 1.1 billion people can speak Mandarin today. About 900+ million learned it in early childhood (mainly in mainland China), and a further 200–300 million use it as a second language for school, work, trade, or family links.

Beyond the Chinese mainland , large Mandarin-speaking populations live in Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia (Chinese schools / heritage learners), North America, Europe, Australia, and Africa (linked to infrastructure and trade projects). Overseas Chinese communities total an estimated 45+ million (various demographic syntheses; UN migration data).

The map below highlights the global distribution of Chinese speakers and the relative scale of usage in different countries:

- Dark Blue = Chinese is the primary national language

- Green = Over 5 million speakers

- Light Blue = Over 1 million speakers

- Pale Blue = Over 500,000 speakers

- Pink = Over 100,000 speakers

- Blue = Countries with major Chinese-speaking communities

- Gray = Countries where Chinese is not widely adopted

The Chinese mainland and Taiwan

The Chinese mainland has about 1.41 billion people. Government surveys report a Putonghua (Mandarin) proficiency rate a little above 80%. That implies roughly 1.1+ billion people can speak it to some degree, though accent and fluency vary. Urban youth often use it as their everyday home language; in many rural or older communities a local variety still leads at home.

Taiwan’s population (≈23.6 million) is almost universally able to understand and speak Standard Mandarin (Guoyu). Many families, however, also use Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, or Indigenous languages. Younger people often mix Mandarin with local words online.

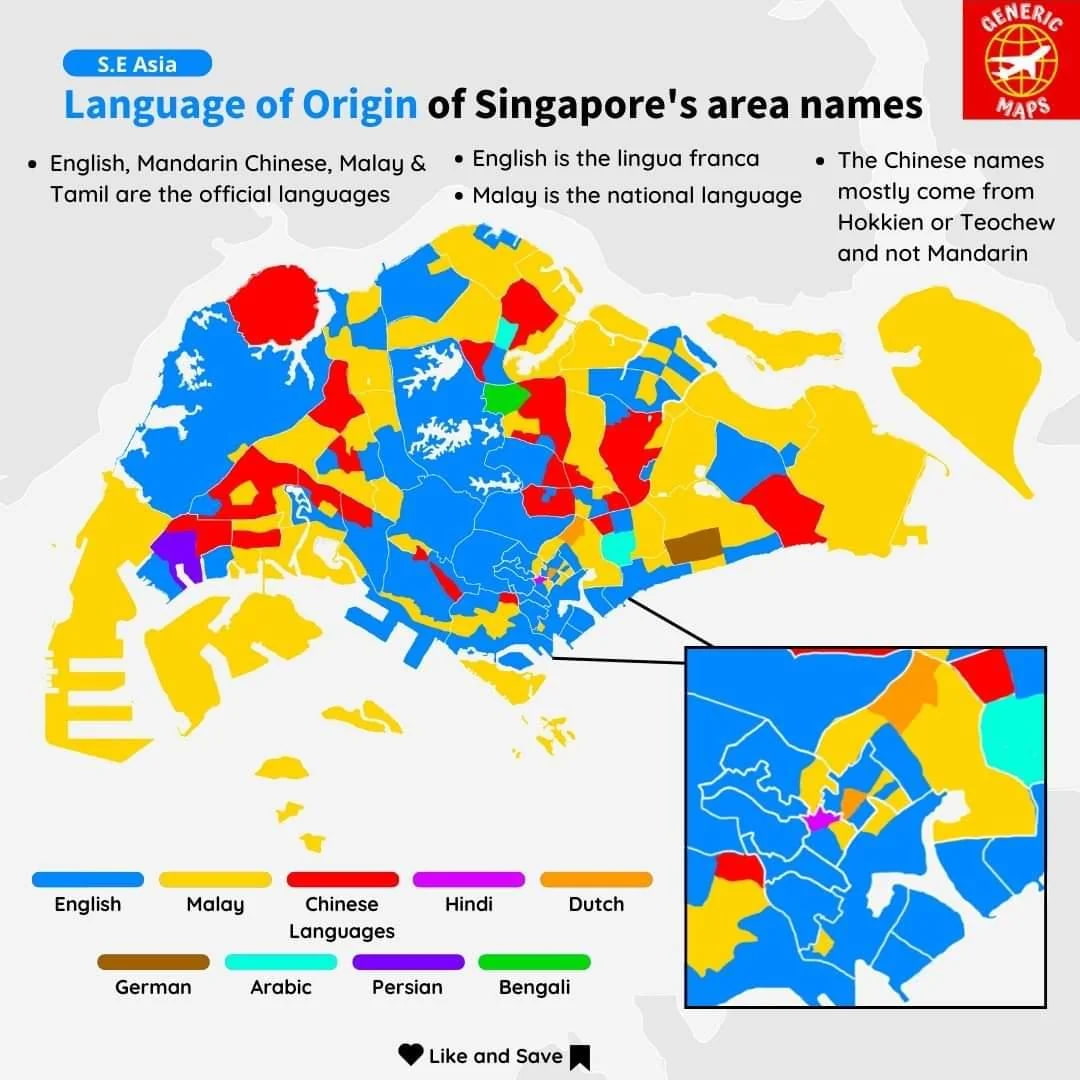

Singapore

Mandarin is one of Singapore’s four official languages and remains central within the Chinese community, which makes up about three-quarters of the country’s 5.9 million residents.

Nearly all ethnic Chinese Singaporeans acquire Mandarin through schooling, yet only around 1.3–1.5 million still use it as their main home language, with English increasingly dominant among younger generations.

Singaporean Mandarin exists in two forms: Standard Mandarin, used in schools, media, and official settings, and Colloquial Mandarin (Singdarin), shaped by English, Malay, Tamil, and Chinese dialects such as Hokkien and Teochew.

The Speak Mandarin Campaign of 1979 replaced dialects as the common tongue among Chinese Singaporeans, but since the 2010s English has grown as the preferred home language.

The Speak Mandarin Campaign of 1979 replaced dialects as the common tongue among Chinese Singaporeans, but since the 2010s English has grown as the preferred home language.

Historically influenced by Taiwanese Mandarin and local dialects, Singaporean Mandarin later aligned more closely with mainland Putonghua through the adoption of pinyin, simplified characters, and immigration. Despite these shifts, it continues to preserve distinctive vocabulary and expressions that reflect Singapore’s multilingual environment.

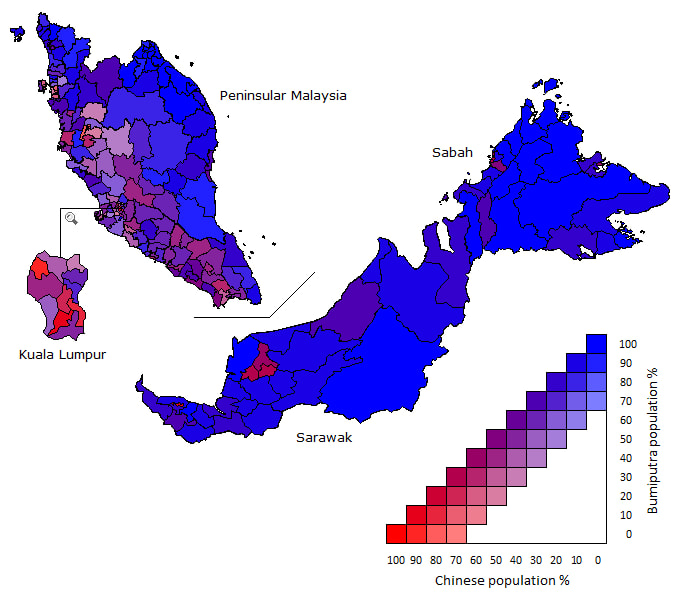

Malaysia

Malaysian Mandarin is the main language of communication among Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese community, who make up about a quarter of the population. Nearly all Chinese families use some form of Chinese at home, with Mandarin gaining prominence through education, although speakers often code-switch with Malay and English in daily life.

Its phonology reflects strong influence from Southern Chinese dialects such as Cantonese and Hokkien, giving it a distinctive “clipped” sound and features like glottal stops and tonal flattening.

Source: Chinese people in Malaysia

Historically, Chinese migration from the Ming and Qing dynasties brought Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, Teochew, and Hainanese to Malaya, with no common lingua franca at first, so Malay was often used for intergroup communication.

Over time, Mandarin became standardized through Chinese-medium schools, though local variants and loanwords persisted. Today, Malaysian Mandarin remains distinct from Putonghua, Singaporean, or Taiwanese Mandarin, shaped by its multilingual environment and the historical layering of Chinese dialect communities in Malaysia.

Europe

Europe hosts an estimated 2.5–3 million ethnic Chinese (migrants, families, students). Older communities sometimes centered on Wenzhou or Cantonese speech, but newer arrivals from northern and inland China boost everyday Mandarin use. Add university learners and business professionals, and Europe likely has 1.5–2 million functional Mandarin speakers. Major hubs: the UK, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and Germany.

The United States

The US has over 5 million people of Chinese origin. Historically many spoke Cantonese or Taishanese; migration since the 1990s (plus students) has shifted the balance toward Mandarin. A reasonable broad estimate is 3.5–4 million people in the US today can speak Mandarin (heritage speakers, recent immigrants, students, plus non-Chinese learners). Usage concentrates in California, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and university towns.

Is Mandarin difficult to learn?

The U.S. Foreign Service Institute classifies Mandarin among its most time-intensive languages for English speakers (Category V, ~2200 class hours) (FSI). Primary obstacles: tonal perception/production, character acquisition and retention, lexical homophones, and discourse-level ellipsis.

Conversely, the absence of verb conjugation, plural inflection, and grammatical gender simplifies morphology. Efficient paths leverage frequency-based graded character lists (e.g., HSK syllabi), chunk learning, spaced repetition, and early integration of authentic multimodal inputs.

Historical Formation of Mandarin Chinese

Modern Standard Chinese draws primarily on the Beijing dialect’s phonology layered over a supra-regional “Northern Mandarin” grammatical and lexical base. Republican-era “National Language” reforms (early 20th c.) initiated codification; mid-20th-century language planning in the PRC intensified promotion through universal education, broadcasting, and literacy campaigns.

Chinese Writing System: Characters, Scripts, and Romanization

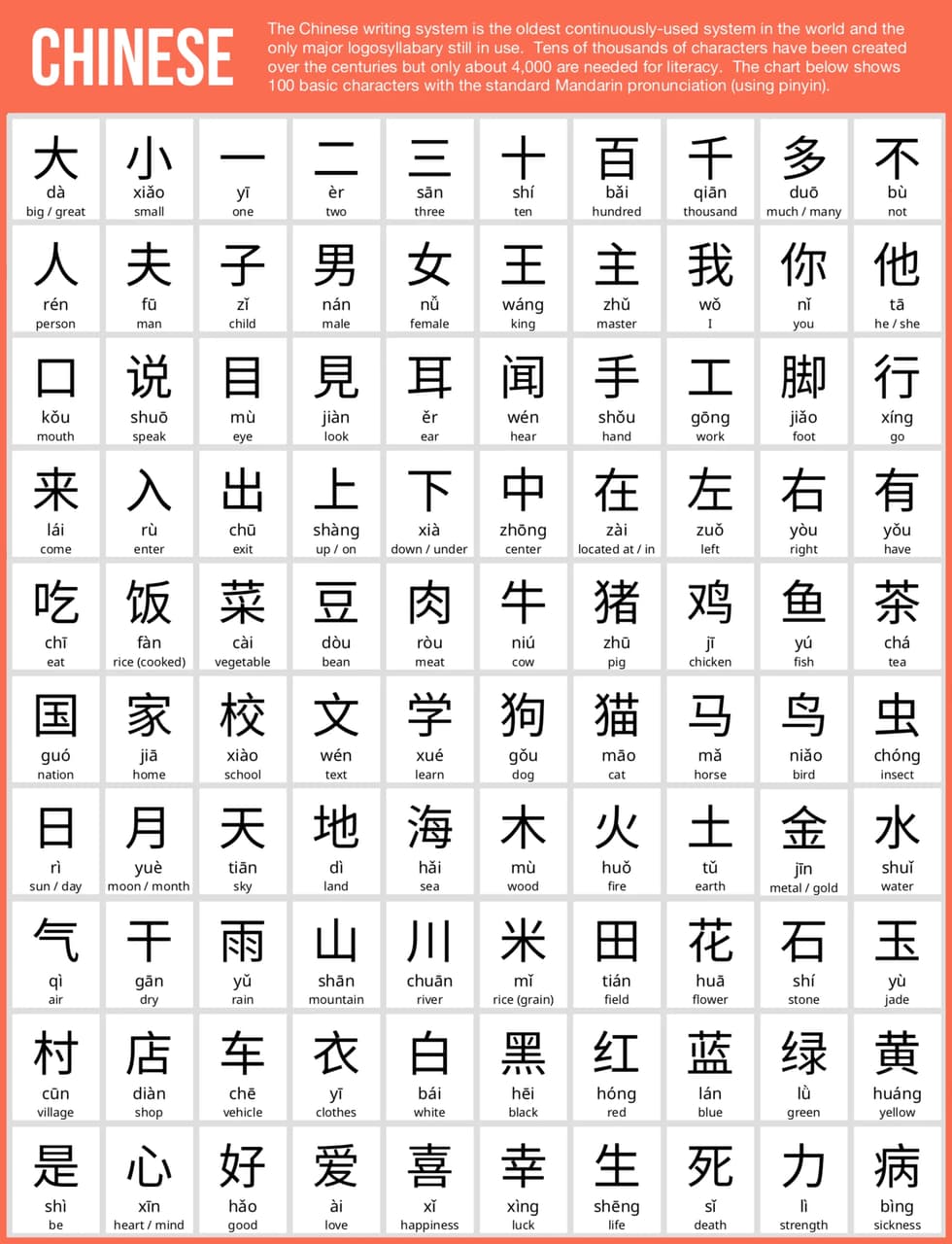

Chinese Characters (Hanzi)

Mandarin Chinese uses Chinese characters (汉字, Hanzi), which are morphosyllabic: each character generally corresponds to a single syllable and a morpheme. The majority of characters (around 80–85%) are phono-semantic compounds, combining a semantic component (radical) that hints at meaning and a phonetic component that suggests pronunciation.

Simplified characters were promulgated in the Chinese mainland (phased mid-1950s onward) to raise literacy; For example, 學 → 学 (study/learn) and 體 → 体 (body). Traditional characters remain standard in Taiwan Province, Hong Kong SAR, and much of the diaspora. Cross-script conversion is not purely mechanical.

Key features:

- Ideographic aspect: Some characters represent abstract concepts directly, e.g., 山 (mountain), 日 (sun).

- Compound formation: Characters can combine to form words, e.g., 电话 (diànhuà, “telephone”) combines 电 (electric) + 话 (speech).

- High homophony: Many syllables share the same pronunciation, making context crucial for understanding.

Source: Chinese character examples

Romanization: Hanyu Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin was officially adopted in the late 1950s as the standard romanization for Mandarin. It serves multiple functions, including teaching Mandarin pronunciation to learners, ordering dictionaries and textbooks, and supporting NLP tokenization, search engine optimization, and text input.

Pinyin represents consonants, vowels, and tones—for example, mā, má, mǎ, mà—and has become a global standard for learning and typing Chinese.

Advantages and Challenges

Key Advantages

- Consistency across dialects: One written system enables communication between speakers of mutually unintelligible regional varieties.

- Semantic clues: Radicals and components within characters offer hints about meaning, aiding learners in recognizing and understanding unfamiliar words.

- Cultural continuity: Chinese characters preserve centuries of literary, philosophical, and artistic traditions, connecting modern readers with historical texts and cultural heritage.

Challenges

- High memorization load: Functional literacy requires learning thousands of characters, with roughly 2,500–3,500 characters needed for everyday use. Each character has its own form, meaning, and pronunciation.

- Homophones and context-dependence: Many syllables share the same pronunciation but differ in meaning, requiring learners to rely heavily on sentence structure and semantic cues to correctly interpret texts.

- Digital input challenges: Typing Chinese requires input methods (e.g., Pinyin, Wubi), which can slow down text entry for beginners and require additional memorization of keystroke patterns or character selection skills.

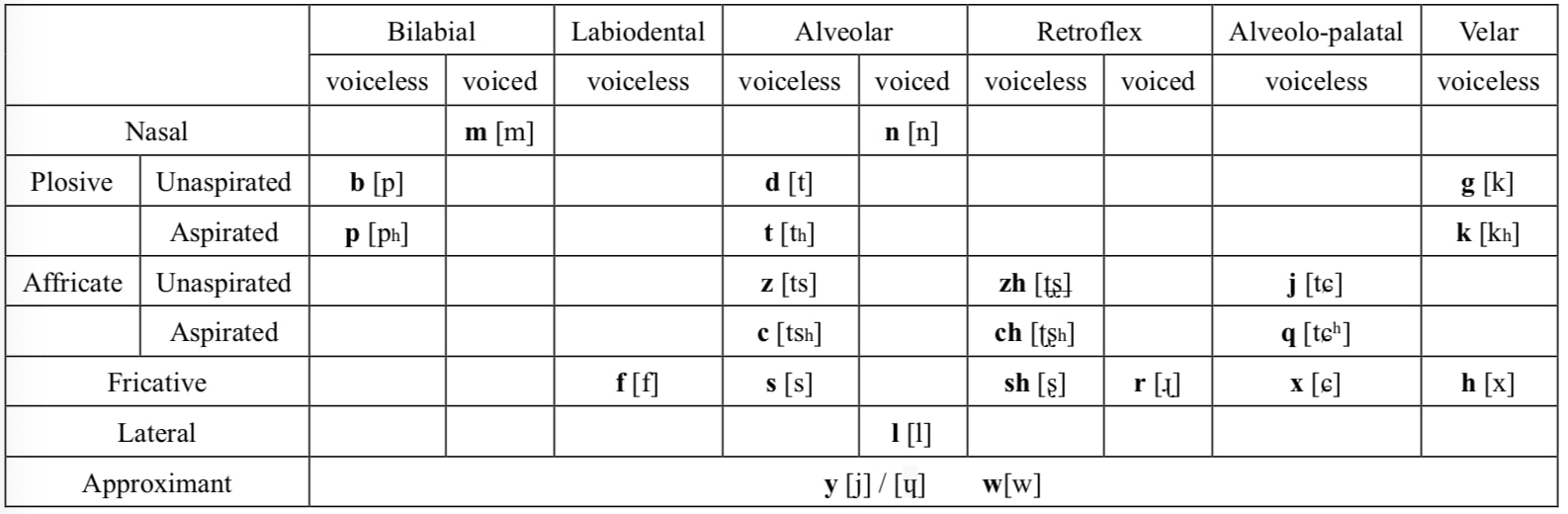

Mandarin Sounds, Syllables, and Prosody

Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language. Each syllable usually has an optional initial consonant, an optional medial glide, a vowel or diphthong, an optional coda (-n/-ng), and a lexical tone.

Key Points:

- Consonants: 21 initials, including plosives (b, p, d, t, g, k), affricates (j, q, zh, ch, z, c), fricatives (f, s, sh, r, h), nasals (m, n, ng), and lateral (l). Some syllables start with a vowel. Key contrasts: aspiration (p vs. b) and retroflexion (zh, ch, sh, r).

- Vowels: six simple vowels (a, e, i, o, u, ü), diphthongs (ai, ei, ao, ou, ia, ie, ua, uo, üe), and nasal codas (e.g., an 安, ang 昂).

- Tones: four main tones (high, rising, dipping, falling) plus neutral. Tone sandhi (notably third tone) and erhua (-儿) cause contextual changes.

- Prosody: syllable-timed rhythm, with intonation marking questions, statements, and emphasis. Two-character units form natural prosodic chunks, key for TTS and subtitles.

- Regional variation: especially in sibilant contrasts (sh vs. s), affecting pronunciation and ASR accuracy.

Source: Check all about Mandarin Phonology here

Sound Translation into Mandarin Chinese

Word segmentation & sentence length: Spoken input lacks clear boundaries; Chinese sentences carry high information density, while translations from other languages can be shorter, causing unnatural pacing.

- VMEG solution: Advanced audio-aware tokenization and dynamic duration adjustment ensure accurate segmentation and natural speech tempo.

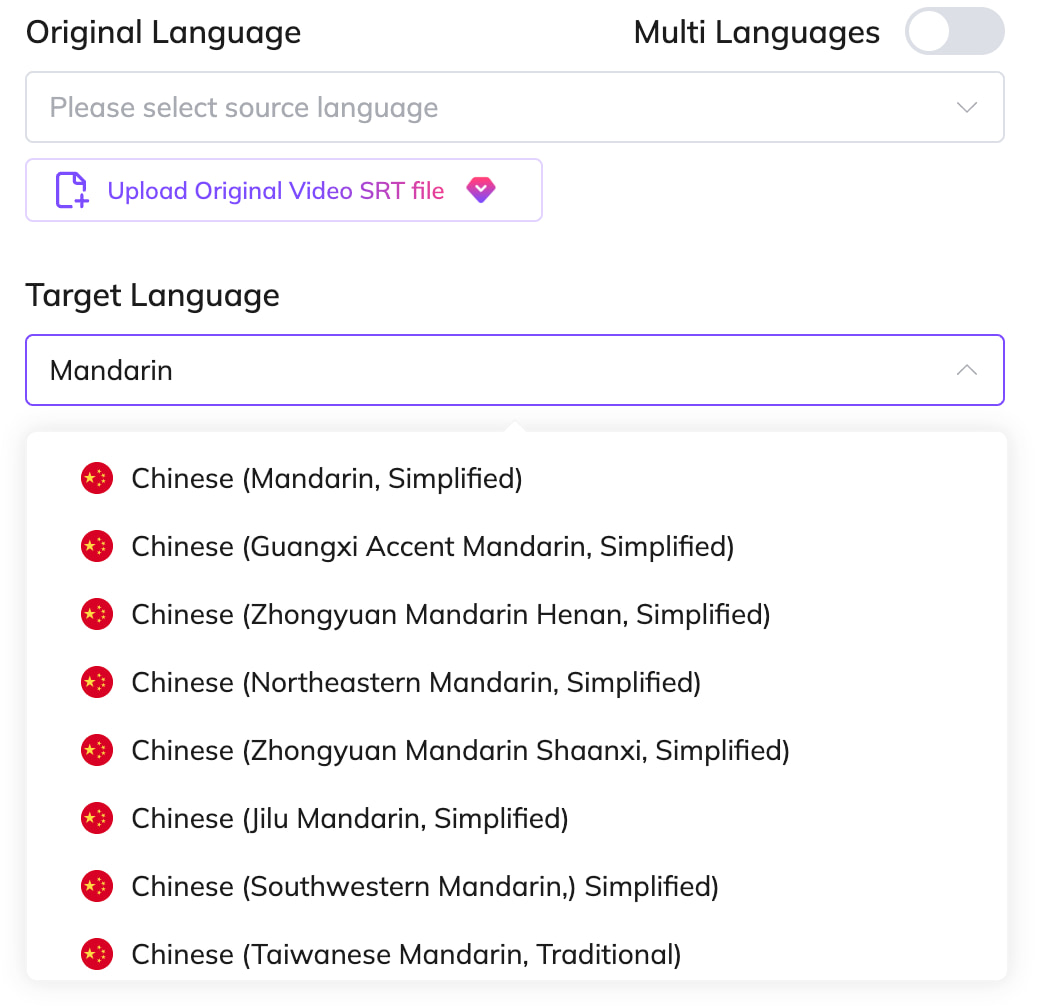

Simplified vs. Traditional & dialect diversity: Need to choose output script, adapt lexical choices, and handle multiple Mandarin dialects (Henan, Shaanxi, Guangxi, Northeastern, Southeastern, Ji–Lu, Taiwanese, etc.).

- VMEG solution: Supports Simplified and Traditional output and full coverage of major dialects for precise video localization.

Tone, politeness & intonation: Speech registers (formal vs. informal) and emotion need contextual adjustment; Mandarin prosody is complex.

- VMEG solution: Neural models restore emotion and intonation with voice cloning, adjust formality, and produce natural-sounding speech.

Numbers, cultural references & idioms: Spoken numbers, symbolic terms, idioms, and colloquialisms require culturally aware adaptation.

- VMEG solution: Context-aware MT, curated lexicons, and adaptive paraphrasing preserve meaning, style, and cultural nuance.

Terminology consistency & cross-variety conversion: Domain-specific terms and Chinese variety switching (Cantonese, Hokkien, Shanghainese, Mandarin) must be accurate.

- VMEG solution: Integrates domain termbases, translation memories, and inter-variety conversion for consistent, precise video dubbing.

Quality evaluation: Accuracy, style, term consistency, and pronunciation must be ensured.

- VMEG solution: Multi-level audits including character-level checks, term consistency, style compliance, and pronunciation verification.

Practical FAQs about Mandarin Chinese

Q1. Are Mandarin and “Chinese” the same?

A1: “Chinese” is an umbrella; “Mandarin” is the standardized national spoken variety used in education and media.

A1: “Chinese” is an umbrella; “Mandarin” is the standardized national spoken variety used in education and media.

Q2. Can Pinyin replace characters?

A2: Pinyin aids learning and indexing but characters disambiguate homophones and carry morphological/semantic cues.

Q3. Is Simplified vs. Traditional a one-click conversion?

A3: Partial—lexical, cultural, and idiomatic differences frequently require editorial review.

Q4. Why so many “dialects” are mutually unintelligible?

A4: Centuries of divergent sound change and lexical evolution under a shared classical written tradition.

VMEG Mandarin Chinese Translator

Ready to engage over a billion Mandarin users with authentic linguistic and cultural precision? Leverage VMEG’s Mandarin video translation, voice cloning, and lip sync to streamline go-to-market.